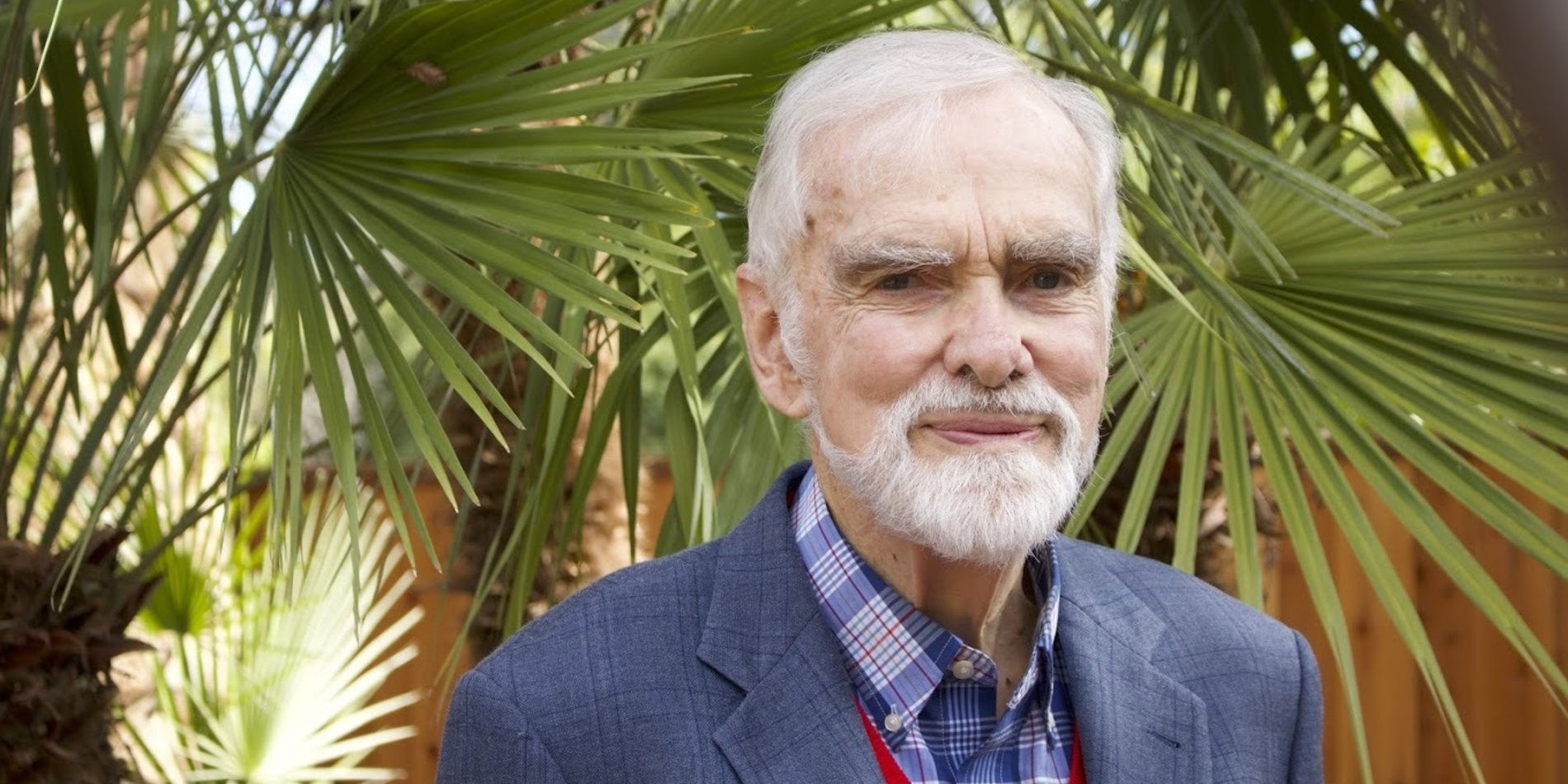

Charles Steele, expert in a wide range of scientific areas, has died

Charles R. “Chuck” Steele, professor emeritus of mechanical engineering and of aeronautics and astronautics, and an expert in wide-ranging scientific subjects, died Dec. 9 at the Kaiser Permanente Medical Center in Redwood City. He was 88.

Steele earned his doctorate under Professor Wilhelm Flügge in engineering mechanics – the study of the physical properties of fluids and solids – in 1960 at Stanford, where he focused on hollow shell-like structures, such as those comprising missiles and boilers. While finishing his degree, and immediately thereafter, Steele worked in industry, notably as a research scientist for Lockheed Research Laboratory in Palo Alto, where he supported the development of the Polaris missile. He also lectured at the University of California, Berkeley, before joining the Stanford faculty in the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics in 1966. He also joined the Division of Applied Mechanics in 1971, where he was on faculty until his retirement in 2004.

Steele first gained notice at Lockheed as an expert in the study of thin-shell structures of aircraft using asymptotic analysis. Soon, however, Steele became interested in the biological implications of his research, broadening the scope of his studies to become one of the world’s leading experts in the mechanics of the cochlea, the structure of the inner ear, which turns physical energy of sound waves into electrical impulses that allow humans and most other mammals to hear.

“That leap from engineering to biology is remarkably rare professionally and, really, a reflection of who Charles was,” said Anthony Ricci, a professor of otolaryngology at Stanford School of Medicine and a frequent collaborator and co-teacher with Steele. “Biology is a lot messier than mechanics, and that uncertainty can be hard for an engineer, but not Charles. He had an intellectual fire and that carried through to the end. He was a force of nature at 80; I can’t imagine what he was like at 30.”

Steele’s first paper on the cochlea was published in 1974 and many of his subsequent works on the topic are still cited today. In fact, he remained academically active until very recently, graduating two PhDs in 2018, mentoring postdocs and publishing his last article, on the inner ear of mice, just this year.

In the late 1970s, he added another vastly different discipline to his repertoire, developing ways to non-invasively measure bone strength to diagnose osteoporosis. Then, in the 1990s, he layered on yet another, researching the mechanics of plant growth.

In total, it is estimated Steele published some 100 journal articles, five review articles and numerous abstracts in conference proceedings, while delivering guest lectures around the world. As an editor, he was perhaps even more influential, becoming editor-in-chief of the International Journal of Solids and Structures, one of the foremost journals in applied mechanics, in 1985. His second wife, Marie-Louise Steele, who died in 2009, worked closely with him on the journal and was instrumental in making it highly successful.

As teacher, Steele was similarly admired. He taught plates and the aforementioned shell structures, differential geometry and the mechanics of hearing to graduate students, and statics, dynamics and mechanics of materials to undergrads. He mentored more than 70 doctoral students through their dissertations and maintained contact with many of them throughout their careers.

“I was not his student, but I learned a lot from Charles in the 20 years we worked together,” recalled one-time Stanford colleague Sunil Puria, who is now at Harvard University. “He was my primary collaborator, but really he mentored all of us. Just this year, we collaborated on a paper. He provided constructive feedback only a few weeks ago. Amazing! He gives us hope as we ourselves get older, that we can do good science late into life. He was a gentle soul and I miss his calm demeanor.”

Professional recognition followed these accomplishments. He was elected a fellow of American Society of Mechanical Engineers in 1980 and the American Academy of Mechanics in 1985. In 1995, he became a member of the the National Academy of Engineering. In 1988, the National Institutes of Health bestowed the Claude Pepper Award upon Steele for his work in hearing.

“He was highly regarded in four different disciplines. How many researchers can say that? When you add in his influence as a mentor and editor, his career stands out,” said longtime friend and fellow Stanford Professor Emeritus George Springer. “But beside that, he was just the nicest person you can imagine. I will miss him. Stanford will miss him.”

Steele’s personal interests were also wide-ranging. He was invited to try out for the varsity basketball team at Texas A&M, though he declined to focus on his studies, and was known to love a Stanford football game. He was an avid birder, as well. He also loved opera and played French horn with the Peninsula Symphony for decades.

Charles Richard Steele was born August 15, 1933, in Royal, Iowa, to Edwin and Ruth Steele, but grew up in Fort Worth, Texas. He earned his Bachelor of Science degree in mechanical engineering from Texas A&M University in 1956 and his PhD from Stanford in 1960.

He is survived by wife Kelly Zhang Steele and stepchildren Jackson of San Mateo, and Alexandra of Berkeley. He survived his first wife, Gail Steele, who died in 1970, and second wife, Marie-Louise Steele, who died in 2009. Steele is also survived by his son Eric Steele and wife Turian (Theresa) Steele and their children Wanittha (Oum) Thapanakul, Kritsada (Ed) Thapanakul and Piyada (Ann) Thapanakul of Seattle; son Brett Steele and wife Tamera Dorland of Alexandria, Virginia, and their children Ian Williams of Washington, D.C., and Elizabeth Williams of Canberra, Australia; son Jay Steele and wife Ilze Duarte of Milpitas, and daughters Julia Steele of Santa Cruz, and Jessica Steele of Milpitas; and son Ryan Steele and wife Andrea Steele and children Carmen, Gaby and Alex Steele of San Francisco.

A celebration of life is scheduled for noon-2 p.m. Feb. 18 at a private residence on campus. In lieu of flowers, donations to The Professor Charles Richard Steele Memorial Fund can be made to Stanford University. Please contact Suzanne Morze for assistance in making your gift, smorze@stanford.edu.