Researchers gain new insight into how breast cancer spreads

For decades, breast cancer was believed to be a disease that was purely genetic in origin.

Mutations and other changes in DNA lead a cell to replicate uncontrollably. A tumor forms, then metastasizes.

However, recent science is upending this notion by showing that the surrounding microenvironment plays a major role in tumorigenesis. For example, something so seemingly innocuous as the stiffening of surrounding tissue, which is commonly observed in breast cancer, plays a key role in driving breast cancer progression.

Now, researchers at Stanford University say they can explain why. In experiments, they introduced mammary cells into what they term “high-stiffness environments” and showed that even healthy cells begin to proliferate and to migrate when stiffness increases. Unchecked growth and movement to other parts of the body are two key characteristics of malignancies. Their findings appear in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering.

While not dismissing genetics as a pathway to cancer, Ovijit Chaudhuri, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering and senior author of the study, says some forms of breast cancer respond to physical as well as chemical cues. “It’s not just what’s inside the cell that matters,” he says. “The neighborhood plays a key role, too.”

The researchers believe that the mechanical stiffness of the microenvironment changes the cell’s “epigenome.” The epigenome is a catchall term for the complex processes and biochemical changes that regulate genetic expression — the turning on and off of genes to produce or impede important biochemicals.

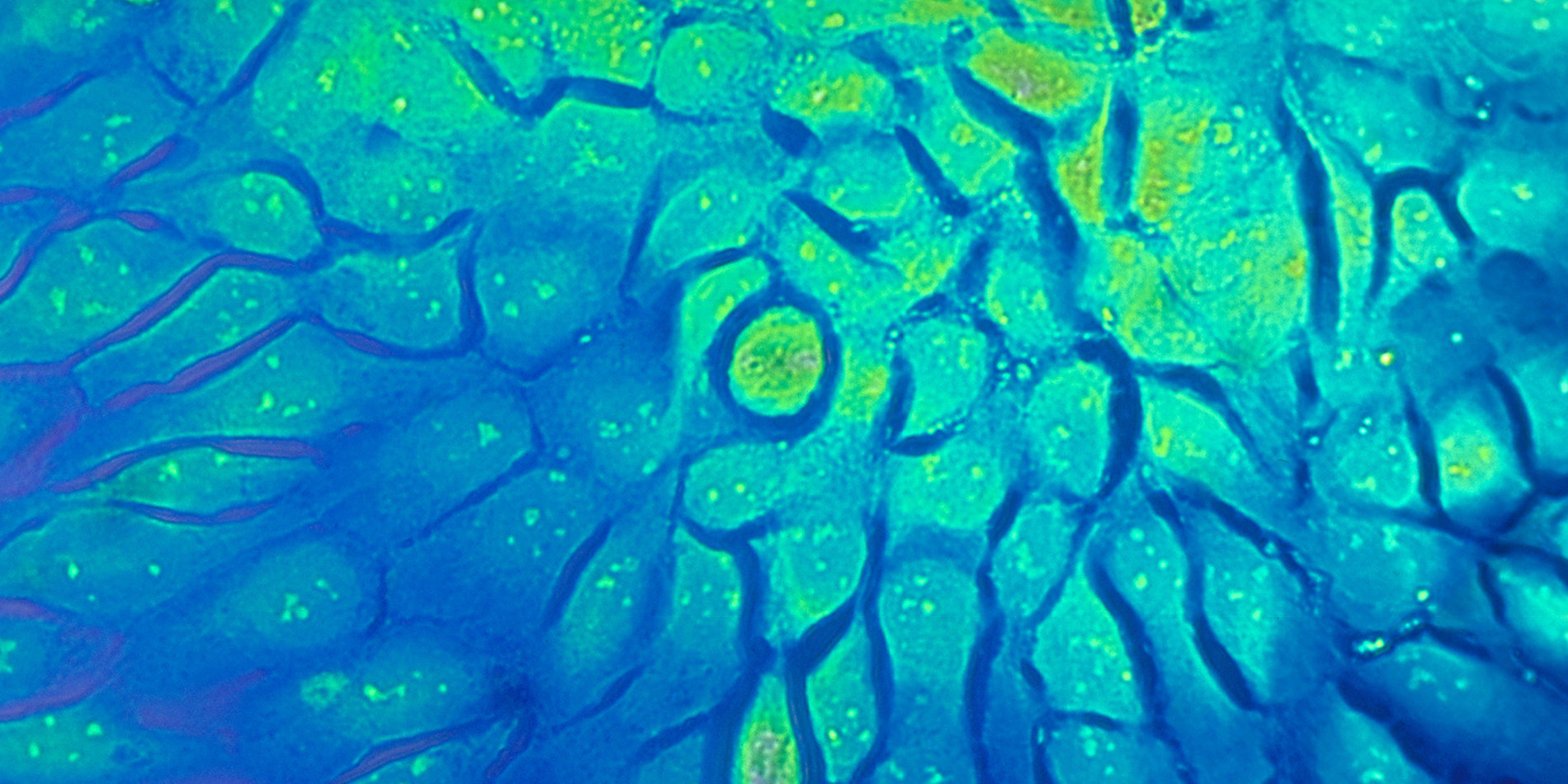

This hypothesis would explain how an otherwise normal cell without genetic changes can behave like a cancer: In any given cell, every strand of DNA must fold upon itself again and again in a highly organized manner merely to fit inside the cell’s nucleus. Cells, meanwhile, are continuously tugging and teasing against their surrounding materials, which changes how the DNA folds. Stiffness, the researchers surmise, alters the way DNA is stored within the cell nucleus, thereby changing what genes a given cell is able to express and, as a consequence, how the cell behaves. Chaudhuri and Ryan Stowers, a postdoctoral scholar in Chaudhuri’s lab and first author of the paper, showed that, with increasing stiffness, some 1,600 sites in the genome become more accessible.

“A gene can only be expressed if it can be accessed,” Stowers says.

In this process of exposing or hiding genes, stiffness can cause a cell to produce new and different chemicals that change how the cell behaves. “That’s how a healthy cell begins to act like a cancer cell,” Chaudhuri says.

With this knowledge in hand, the question then turns to how scientists might use this new information to better understand how cancers form and, eventually, to find new ways to fight cancer.

Chaudhuri says this research is promising in a few regards. First, the link between the physical microenvironment and the epigenome inside the cell represents a new avenue to study cancer, offering up enticing new targets for drugs that might slow or halt the growth of cancerous cells. For example, their study identified a molecule critical for sensing stiffness and driving malignant behaviors, which acts by binding to the DNA that is opened up by increased stiffness.

Though the researchers focused on breast cancer in this study, they have reason to believe that microenvironmental stiffness plays a factor in other solid-tumor cancers, like those in the lungs, brain, bone and liver. They look forward to exploring those connections in future work.

These new findings could even improve the study of cancers. Typically, researchers do experiments with lab-grown cells, which are cultured in traditional petri dishes. Such tools, he says, are too stiff. They don’t accurately mimic the conditions such cells would normally experience inside the body and raise the specter of misleading results. Instead, Chaudhuri encourages researchers to culture tissues using new hydrogels that are engineered to more closely match the physical environment of the human body.

“Getting as close to the natural environment is key to better understanding of cancer,” he says.

The following Stanford researchers also contributed to this study: Michael Snyder, professor of genetics; Anshul Kundaje, assistant professor of genetics and of computer science; Mary Teruel, assistant professor of chemical and systems biology; graduate students Anna Shcherbina, Johnny Israeli, Julie Chang and Sungmin Nam; and postdoctoral fellows Joshua Gruber and Atefeh Rabiee.