Turbulence influences the world – and turbulence research is providing advanced understanding of the complex phenomenon

Beverley McKeon calls turbulence “a hidden physics” – a phenomenon many people don’t think about beyond bumpy plane rides, but which underpins a multitude of grand science and engineering challenges.

Turbulence, a subset of fluid mechanics, shapes how water passes through pipes, pollutants spread through the air, blood flows through veins, currents mix in the ocean, and any other situation where liquid or gas moves fast enough for chaotic motion to emerge.

“It goes from the sublime to the ridiculous in terms of engineering interest,” said McKeon, a professor of mechanical engineering and program director of Stanford’s Center for Turbulence Research, or CTR. “A pipe is not super exciting, but then if you think about, say, landing on Mars, that’s almost entirely aerothermal fluid dynamics.”

Stanford researchers have studied turbulence in laboratory experiments since the 1960s. They began using the most advanced supercomputers in the 1970s, when computers became powerful enough to start modeling turbulence. Director Parviz Moin, the Franklin P. and Caroline M. Johnson Professor in the School of Engineering, founded CTR in 1987, and it has since become a global leader in understanding turbulent flows – described by well-known physicist Richard Feynman as “the most important unsolved problem of classical physics.”

Today, CTR’s interdisciplinary researchers in the School of Engineering and the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability are pushing the field into new frontiers, answering questions and solving problems that benefit people and the planet.

Advances in turbulence

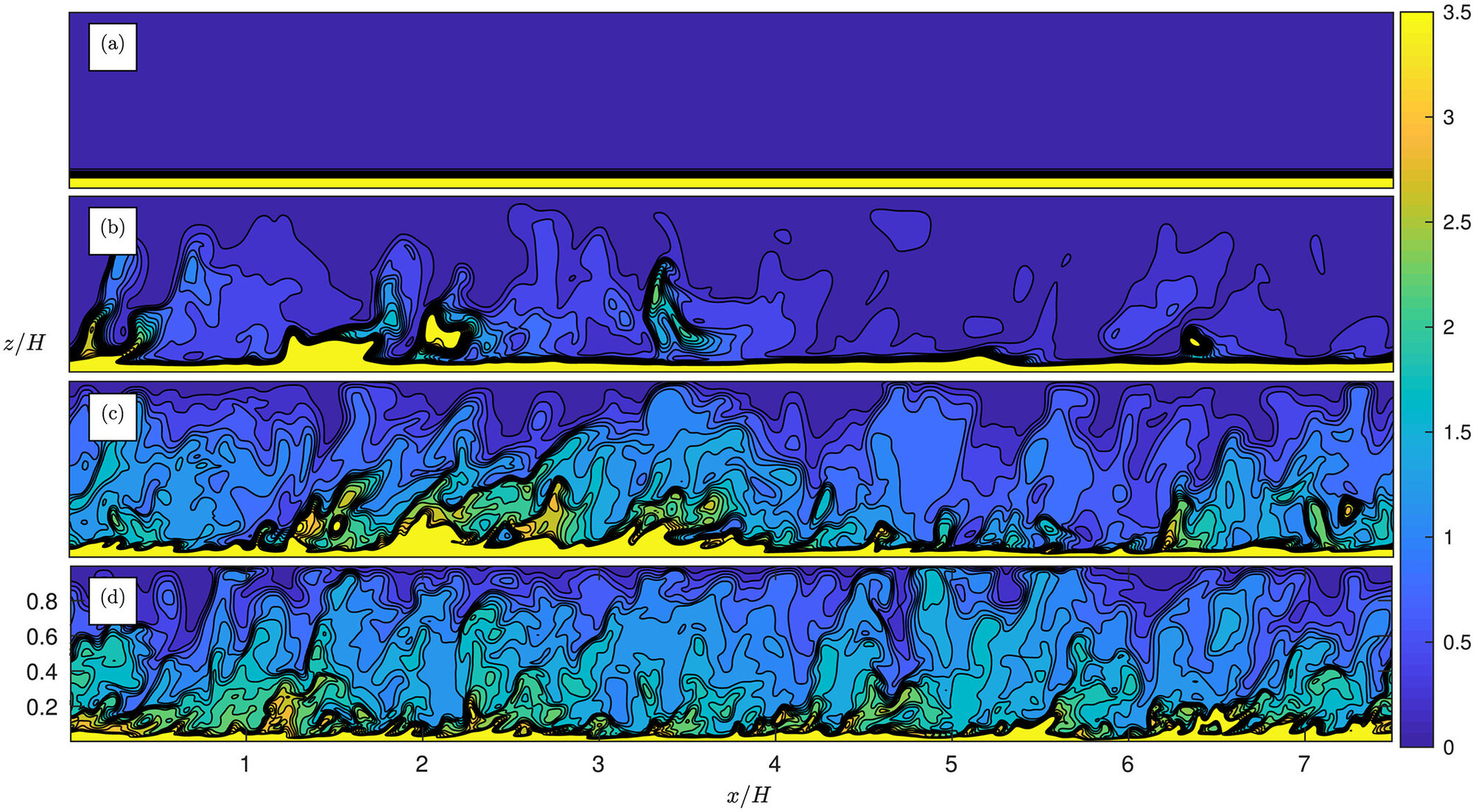

Scientists have known the partial differential equations that govern fluid flow for more than a century but solving them on paper has been nearly impossible. Because flow is chaotic and varies in three dimensions over time, simulating it requires fast, powerful supercomputers.

Modern turbulence research involves complementary techniques in computation and experimentation. Research capabilities in both areas have advanced dramatically, especially in the past decade.

Supercomputers are now “providing the microscope that you need to look into the details of turbulent flows in the same way a biologist would use microscopes for looking at very small cells,” Moin said.

Advanced algorithms and graphic processing units enable precision modeling: for example, simulating airflow around a full aircraft during takeoff. These simulations are now part of the design cycle for things like airplanes, racecars, and turbines, replacing prototyping steps and saving companies time, energy, and money, Moin said.

McKeon said CTR’s laboratory facilities allow researchers to visualize turbulent flow in ways that are, for now, out of reach of the biggest supercomputers. For example, one facility includes a wind tunnel inside a pressure tank with diagnostics that can measure down to 4 microns. Other facilities can create “digital twins,” where experiments run parallel to computation.

CTR’s computational and experimental capabilities are empowering researchers to investigate new problems, Moin said.

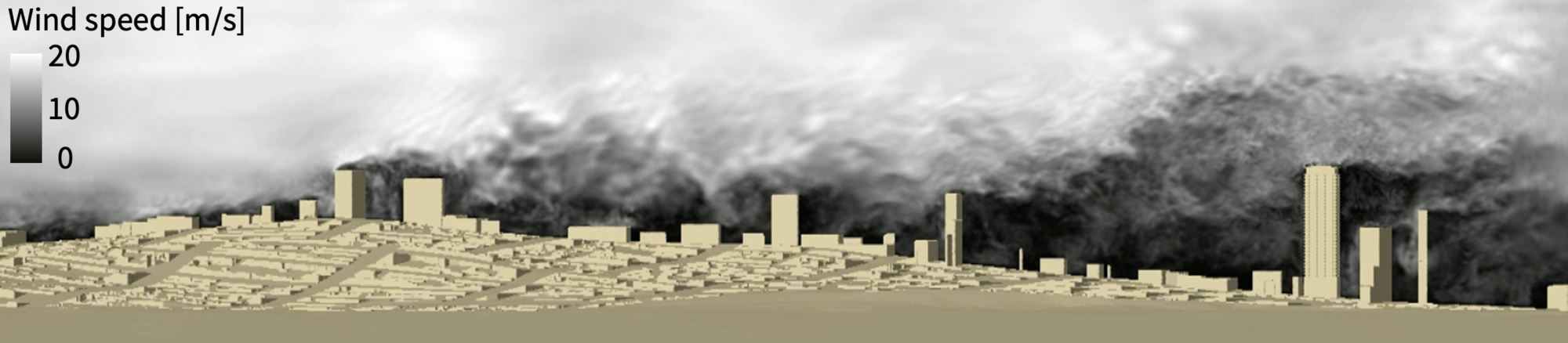

For example, Catherine Gorlé, an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering – a joint department of the School of Engineering and the Doerr School of Sustainability – studies the airflow in and around urban buildings. Applications for her work include understanding the effects of extreme wind on high-rises and designing ways to bring natural ventilation into buildings.

She’s currently using field measurements from San Francisco and Seattle to enhance her lab’s simulations and understand better how variable wind conditions, with variable turbulence characteristics, influence airflow.

“Our goal is to understand what causes the significant variability observed in the field,” she said. “What are the parameters that we should vary in the simulations to represent the reality and all the possible wind conditions that the building really sees?”

Expansion into sustainability

The turbulence field is not only advancing technologically but also expanding into environmental engineering and geophysical sciences. This is especially true at Stanford, where CTR has a strong connection with the Doerr School of Sustainability.

“Taking this knowledge that has been developed here in a singular fashion from 1987 onward and developing and disseminating it for other fields that can benefit from it is an important step forward,” McKeon said.

Although turbulence modeling methods have been applied extensively to simulate flows related to weather prediction and climate, advanced flow and turbulence simulation methods for geophysical flows need greater investment, said Oliver Fringer, a professor of civil and environmental engineering and of oceans.

“Relative to the amount that we know about fluid mechanics of airplanes and engines, we still know little about turbulence and mixing in the atmosphere and oceans,” he said.

Much of Fringer’s research focuses on San Francisco Bay, which recently experienced one of its worst algae blooms. One factor was less sediment flowing into the bay because of droughts, Fringer said. But scientists don’t fully know how to predict the flow of sediment in the future – a problem that depends to a great extent on turbulence in the bay and its impact on the transport of fine sediment grains.

Fringer’s goal is to someday simulate flow in the bay with as much detail as existing models of airplane engines.

If oceanic and atmospheric turbulence receives the interest it needs from the scientific community, innovative research like CTR’s will dramatically increase knowledge of these systems within the next 20 years, Fringer said.

Leif Thomas, a professor of Earth system science in the Doerr School of Sustainability, studies the intersection of fluid dynamics and oceanography.

“Understanding the physics of these turbulent flows is key because they play an important role in regulating Earth’s climate both directly by mixing heat and carbon in the ocean, but also indirectly by affecting biological and chemical processes that draw carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and into the ocean,” he said.

One project examines how turbulent flows affect how marine life adapts to the dynamic environment of the ocean. Working with marine biologist Barbara Block at Stanford’s Hopkins Marine Station in Pacific Grove, Thomas created a simulation of an area of the Pacific that attracts white sharks. He discovered it’s a hotspot for turbulence that drives vertical motion in the ocean – bringing nutrients to the surface to sustain phytoplankton and a thriving ecosystem, which presumably attracts the sharks.

Thomas said he’s excited that turbulence research creates interactions among engineers, physicists, and oceanographers that lead to new insights, especially in understanding the climate system and how humans might adapt to climate change.

“It’s more than just an abstract study of turbulence, even though that’s fascinating,” he said. “Having a deep understanding of turbulence in these systems and also being able to model that turbulence is going to be essential for addressing critically important questions that affect all of us.”

Building the turbulence community

CTR is collaborative by design. The center’s unique postdoctoral fellowships require applicants to propose their own projects rather than work with a specific faculty member. Postdocs are then encouraged to interact and share ideas with other Stanford researchers.

Salvador Gomez, a postdoc in mechanical engineering at CTR since 2023, was inspired to apply after attending CTR’s biennial summer program, which brings together turbulence researchers in academia, industry, and government from dozens of countries to launch new projects. In 2024, more than 100 participants representing 15 countries and 60 institutions worked on projects focused on topics including supersonic combustion, contaminant dispersion, and jet noise – adding to the summer program’s long history of spurring breakthroughs in turbulence research.

“As a participant of the CTR summer program, I found the hosts in CTR extremely welcoming and had the opportunity to surround myself with turbulence researchers who worked on a wide range of problems with state-of-the-art tools,” Gomez said. “In speaking to other participants, I learned that a big reason why researchers who have been involved with CTR in the past decide to come back for the summer programs is because they love the collaborative nature of CTR.”

Within his first week as a postdoc, Gomez started a project with his officemate to predict through reduced-order equation-based models how turbulent structures from the wind interact with the surface of the ocean.

CTR postdocs are also ambassadors beyond Stanford, promoting STEM careers in local schools. The CTR^2 Summer Program invites undergraduate students and community college students to campus to learn about turbulence research.

Gorlé, who also completed a postdoc at CTR, said the center’s collaborative environment is an important part of advancing turbulence research.

“It’s a very broad field, but there’s overlap in the methods and the challenges, so there’s lots of ways to exchange ideas,” she said. “The exchange of ideas and the dynamic environment full of people that are all excited about the same thing make it great to be a part of the CTR community.”