The future of bioprinting

Mark Skylar-Scott is one of the world’s foremost experts on the 3D printing of human tissue, cell by cell.

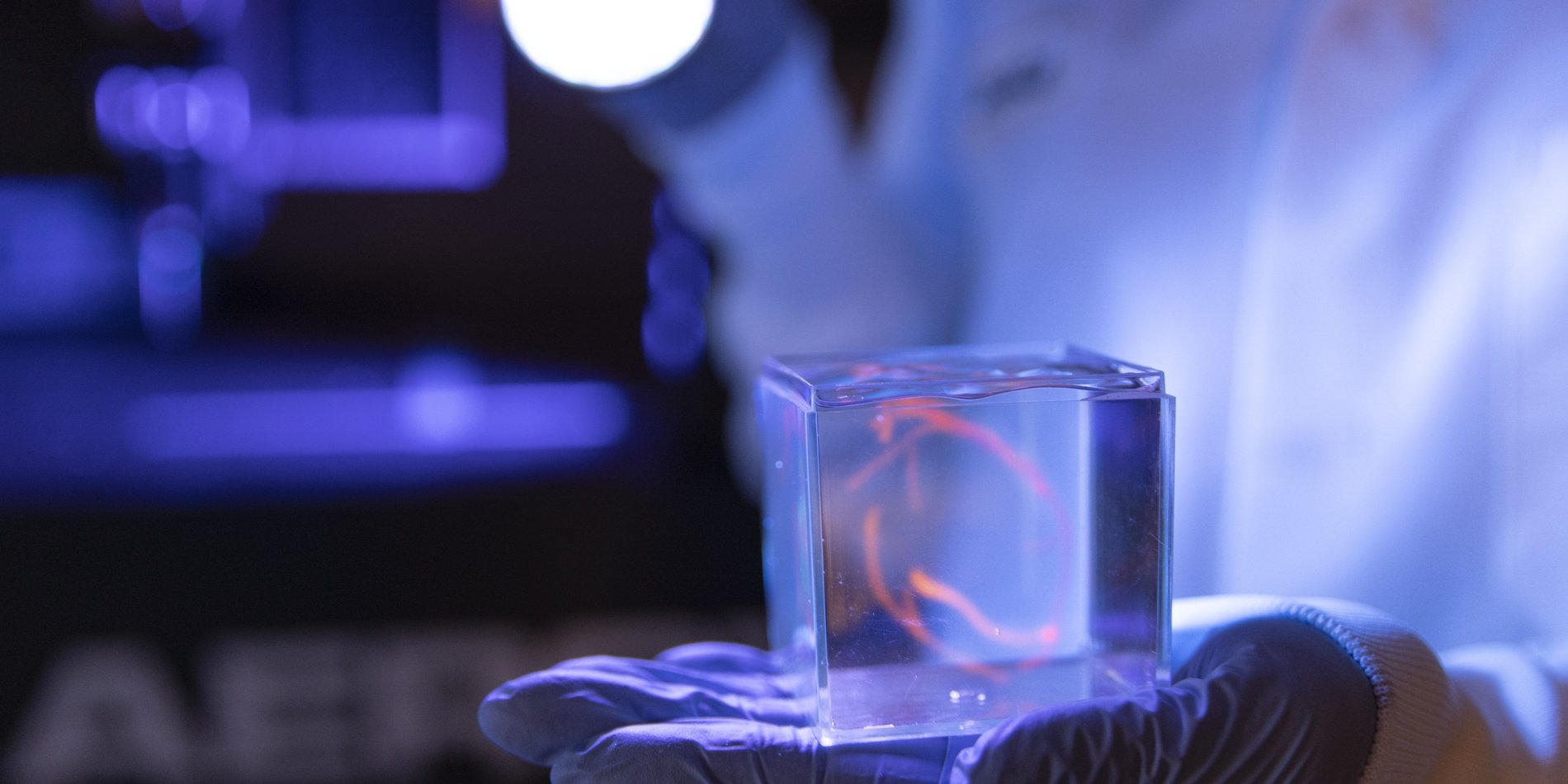

It’s a field better known as bioprinting. But Skylar-Scott hopes to take things to a level most never imagined. He and his collaborators are working to bioprint an entire living, working human heart. We’re printing biology, Skylar-Scott tells host Russ Altman on this episode of Stanford Engineering’s The Future of Everything podcast.

Transcript

[00:00:00] Mark Skylar-Scott: We're really excited about the potential of using bioprinting to produce human tissues and hopefully one day organs on demand. So that instead of having to receive someone else's heart as a donor, you can have your own heart made from your own cells.

[00:00:14] Russ Altman: This is Stanford Engineering's The Future of Everything podcast, and I'm your host, Russ Altman. If you enjoy The Future of Everything, please follow or subscribe wherever you get your podcasts. This will guarantee that you never miss an episode.

[00:00:32] Today, Mark Skylar-Scott will tell us about how his group is trying to develop 3D printing of human tissues and organs. His initial focus is on the heart because it's so badly needed for future transplantations. It's The Future of Bioprinting.

[00:00:47] Before I get started, please remember to follow the podcast if you're not already doing so and hit the bell icon if you're listening on Spotify. This ensures that you'll get alerted to all our of our new episodes and never miss the future of anything.

[00:01:07] You know, many of us are aware of 3D printing that has emerged in the last decade. Usually plastic, sometimes metal, these are amazing little machines that can make 3D objects by laying down layers of material to form the widgets that we all need.

[00:01:23] But now scientists are trying to do the same thing with human cells to create tissues and organs. It's called bioprinting or even 3D bioprinting. This is exciting because it opens up the possibility of developing new tissues to replace our old hearts, our old kidneys, our old cartilage. It sounds like science fiction, but people are starting to do it.

[00:01:47] In fact, Mark Skylar-Scott is a professor of bioengineering at Stanford University. He's an expert at 3D printing, and he will tell us how he's working to create all 11 cell types that are required in a human heart, how he can get them to where they need to be, and how he can make sure that they get the blood that they need so the oxygen and the nutrients allow them to continue to live. Plus, the heart needs to pump and connect to the rest of the body.

[00:02:15] Mark, what is bioprinting?

[00:02:18] Mark Skylar-Scott: Well, you may have heard of traditional 3D printing, where we have nozzles that are extruding plastic to form these, you know, cute little key rings and trinkets and, you know, other exciting gizmos. Bioprinting is instead of printing plastic, what if you're printing cells? You're printing biology?

[00:02:36] Russ Altman: Wow. Okay. So, there's a lot to unpack there. So, in fact, I'm not very familiar with 3D printing, although of course I know it exists and I've seen the little widgets that you describe. Um, I know that a lot of printing in 2D is like inkjet. And so, I guess we'll go a little bit into it right now, and then we can pop up and talk about why we would ever want to do this.

[00:02:56] Tell me about the technology. Are we actually, you said, I think you said the word nozzle. Are we actually squirting biological material kind of on some sort of substrate to get it to assume a 3D shape?

[00:03:08] Mark Skylar-Scott: You, uh, use a word that I often like describing our work in, squirting stuff out of nozzles, that's what we do. So, uh, think of, uh, a traditional 3D printer working with plastic, heating it, and spaghetti-ing it out of a nozzle, and then that spaghetti gets moved around in three dimensions to build up a three-dimensional shape. Um, but instead of plastic, we're spaghetti-ing out, you know, a biopolymer with cells, like a cell friendly material and cells that we put together and construct a three-dimensional biological shape.

[00:03:39] Russ Altman: Okay, great. So, now that we have this rough idea of bioprinting, let's pop up to 30,000 feet. Why are you doing this? What are the big opportunities that you see that have made you kind of literally devote your career to this topic?

[00:03:54] Mark Skylar-Scott: Yeah, so we're really excited about the potential of using bioprinting to produce human tissues and hopefully one day, organs on demand. So that instead of having to receive someone else's heart as a donor, you can have your own heart made from your own cells, right? So, it's a wonderful dream and I think it has been a dream in this field of what we call tissue engineering, making new tissue, for about 40 years now.

[00:04:18] Um, but bioprinters are just the ideal way of making living matter, right? We are three dimensional creatures. And so, the idea of trying to create a living being or a living organ, um, in a 2D Petri dish, right, is not going to work out, we need some three-dimensional structure. And 3D printing is just unlocking the ability to make things much more precisely and get much better biological function.

[00:04:46] Russ Altman: Okay, great. So that's a very exciting, uh, you know, the idea of a transplant where, uh, as many people know, one of the big risks of transplant is rejection, where the immune system basically realizes that donor heart doesn't match the rest of the body and there's an attack on it which can really lead to well rejection of the organ and the need to do something. Uh so that sounds very compelling. Uh now, okay so where are we going to get the cells to uh to print with? So, you said that uh there are these cells, and they might be derived from me so can you take me through, what would be, whenever this is, uh, a possible, what would be the sequence of events that would get me my new heart?

[00:05:27] Mark Skylar-Scott: Yeah, so, traditionally, tissue engineers have relied upon harvesting cells from a patient, like a primary cell, and then growing them up, culturing them so they divide. But if you think about heart cells, they actually don't divide. So, you can't go into the patient and take a biopsy of some of their heart cells, so we rely on going back to stem cells. And fortunately for us, there have been a lot of, uh, you know, advances in stem cell biology in the past 10 years. Where we're now we can take your own skin cell or blood cell, white blood cell and reprogram it, that is turn it into a stem cell, an embryonic like stem cell.

[00:06:05] And this is really exciting because now we have a source of unlimited patient specific cells from you. And these cells, uh, we can divide in a big bioreactor to create giant quantities, vats of these, of these cells. Um, and then we instruct them in these vats to turn into, uh, uh, specific cell types like the heart or other cell types that are present in the heart. Uh, and that forms our raw material that's, you know, can be made up of your own genetically identical cells. So that's really, really exciting for us.

[00:06:37] Russ Altman: So that really is very clear. So, using skin cells that have then be reprogrammed was the word you use. That sounds great. Now, everybody knows that the heart, well, many people know that the heart is made out of bunches of different types of cells. We have the cells that contract, the myocytes, we have the vasculature, the cells that make up the arteries and the veins, there's an electron, uh, electrical signaling system in the heart. So, it sounds like there are multiple cell types. How do you get them in the right place?

[00:07:05] Mark Skylar-Scott: Yeah, this is not easy. So first we have to create them, right? We have to make 11 different cells. And that means...

[00:07:11] Russ Altman: Is it 11?

[00:07:11] Mark Skylar-Scott: ...11 different cells that we're making as part of our big effort to recreate the human heart. And this means we need at least 11 different vats that are instructing the cells to become each of the different cell types. And we need to do that not in a few million-cell scale, but we need billions of these cells. Um, and so that's sort of step one, forgetting the raw material for the printers.

[00:07:34] The second thing we do is then work with a method of 3D bioprinting that we call embedded 3D bioprinting. So instead of printing in air that you may be familiar with a traditional 3D printer where you're kind of extruding material out layer by layer, we're actually printing one material inside a second support material. So, we're printing down into a bath of support gel, and that allows us to work with very soft matter. We're not working with plastic; we're working with stem cells. So, these are not hard, rigid, predictable materials. These are gooey, mayonnaise like consistency of compacted centrifuge stem cells and stem cells derived different cell types. So, we work inside this support bath so that it's able to retain its shape while we're printing, and we can extrude this three-dimensional structure of the different cell types.

[00:08:26] Now, if there's 11 different cell types, then we have to come in with 11 different nozzles, right? To extrude each of these different materials in turn so that we can create the resulting pattern of Do you want me to list them? We can go for it.

[00:08:39] Russ Altman: Yes, let's do it. 11. It's only 11.

[00:08:41] Mark Skylar-Scott: Ventricular cardiomyocytes, atrial cardiomyocytes, arterial endothelial cells, venous endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, macrophages, purkinje fibers, nodal cells, cardiac fibroblasts, epicardial cells, endocardial cells.

[00:08:58] Russ Altman: Okay, so this is so, and I'm imagining 11 nozzles. I love this. 11 nozzles at the right moment and at the right position laying down their material. And I love your analogy with mayonnaise because it's clear that mayonnaise at a certain level, it wouldn't even be able to support its own weight. And so, you talked about a scaffold.

[00:09:17] How do you build that scaffold? Is that some sort of, um, temporary scaffolding? Like when you build a building that eventually gets removed, or will this in fact, become part of the 3D printed organ as well?

[00:09:29] Mark Skylar-Scott: So, the support path we're printing in will not remain part of the tissue. It can be removed at a later point. So, we have a few different materials that others in the field have really pioneered. One of them is literally hair gel, uh, which is quite nice because if you add a little bit of extra salt, it liquefies, um, and you can wash it away.

[00:09:48] Russ Altman: Wow.

[00:09:49] Mark Skylar-Scott: The, and it's very biocompatible and safe and available in massive bulk. Uh, but other ones are using, for example, little microparticles, little, tiny pieces of gelatin that you may know as Jello. Um, and this, you can raise the temperature to 37 degrees and the Jello melts, and then you can melt away the support. So, you basically initiate this gel to liquid transition by changing the temperature or the ionic concentration of salt. Um, and that allows you to then lift out, uh, your resulting tissue.

[00:10:18] Russ Altman: But let me go to this issue of, uh, you have these cells, and I won't say cells have a mind of their own. But cells do have, uh, functions that are kind of built in and that they can do. So, I'm wondering. How much help do the cells give you? Do you have to get it exactly right or will the cells sort things out because they know that they're supposed to be doing a certain thing and they're supposed to have certain neighbors and so do they actually migrate a little bit and organize themselves appropriately or is that too fanciful wishful thinking by Russ and you have to get it exactly right?

[00:10:49] Mark Skylar-Scott: Sorry, it's a little yin and yang to this, right? The good thing is that the cells can do some of the hard work for us at the cell scale, right? Maybe they migrate to find their neighbor and then the heart cells communicate and connect with each other. That's great. But also, cells have a mind of their own and that makes it hard to predict how it's going to behave, right?

[00:11:09] We as engineers often want to instruct biology what to do, but biology is a lot cleverer than I think, your average bioengineer, including myself. Um, so that means that, you know, there's a lot of work involved in really carefully coordinating how those cells behave.

[00:11:25] So I mentioned one of them. Right, when we create this mayonnaise of cardiomyocytes, they need to be liquid like enough that we can print them through a nozzle. But that means that they're not all connected to each other in a tough tissue, right? You can't print heart tissue it's just going to tear and break. Instead, we work with lots of little micro tissues of heart, which independently can kind of flow and form this mayonnaise consistency. But we need it ultimately to become strong and to beat synchronously. And so, for that the cell migration, encouraging these cardiomyocytes to kind of crawl out of their little, tiny tissue and find their neighboring tissue is really important. And that will not only allow it to beat more synchronously, because they're now touching each other, but also allow it to start mechanically connecting. So, it goes from a mayonnaise to a steak like consistency.

[00:12:11] Russ Altman: A steak. So, okay. This is...

[00:12:14] Mark Skylar-Scott: We will not be eating these. These are human cells.

[00:12:16] Russ Altman: No, that's all. Although, as you know, there are colleagues of yours doing very similar things for the purposes of eating, but we won't go there today.

[00:12:23] Are we going to be printing a full-size heart? Or are we going to print like a baby heart and let it grow? And if the latter, would it grow in the so called 3d Petri dish or would you implant it and let it grow in the natural environment where it's going to function?

[00:12:39] Mark Skylar-Scott: That is a great question. We have projects in both spaces.

[00:12:41] Russ Altman: Ohh.

[00:12:42] Mark Skylar-Scott: So, uh, one of our projects is focusing on hearts. We, um, transplantation in the adult, for which we'll be creating a full-size adult heart. And the second is working on a bio pump or something that is able to provide a second ventricle for children born with one ventricle. And for this, because this is an operation the child might undergo in its first one or two years of life and then that will have to grow with the patient.

[00:13:09] Now, I'm going to be quite frank here. No one has tried to make something at this scale out of stem cells and no one can say exactly what these are going to do over a long time period in an animal. It's just not been done at this scale before. So, we hope it might grow with the patient. And there's quite a lot of engineering literature that shows these tissue engineered scaffolds can grow. But not at the necessarily the scale of a whole organ. So, we don't know yet how these are going to respond in vivo. Um. But that's what we seek to, uh, to understand.

[00:13:42] Russ Altman: And I would also imagine that there's a concern, or at least you have to make sure that you can get these things when they are growing to stop growing. So, um, is that a technical challenge? Do you imagine that these cells that are now being encouraged to migrate and grow and form the heart. Is there a risk that they will continue to grow kind of beyond what you really want?

[00:14:03] Mark Skylar-Scott: And that's another great question. So, there's a lot of concerns and everything is a challenge. Um, and yes, making sure that it's receiving the right cues at the right time. So, to some extent, you know, a developing human already provides those cues, right? We grow and know generally when to stop growing and the cells that we produce will presumably sense the same growth factors um, and changes over time that may allow it to sort of stop growing when it should stop growing. I will say that we also intend to start growing this organ, not in vivo, not putting it straight into a patient, but instead have it in a bioreactor that we can control its environment.

[00:14:41] So think about those first few crucial days when we go from a mayonnaise to a steak, right? Why these little pieces of tissue connect together that we expect to do inside you know, large fat reactors, uh, that will hold the whole organ. And we are able to add molecules that dictate which pathways are on or off to encourage more cell migration and then tone that down after the connections have been established.

[00:15:05] Russ Altman: So, I'm gonna guess that you don't go and have your first experiment be 11 different cell types altogether. And correct me if I'm wrong. Um, so can you tell what's the path to the full 11, are there subsets that we, you know, are kind of easier to work with together and then you build up your confidence or in fact, are you indeed going for all 11 at once? I'm just very interested in the sequence of events that lead to success.

[00:15:31] Mark Skylar-Scott: Yeah, so we've already done quite a lot of work at the small tissue scale with small amounts of very manually cultured cells. So, we understand how these roughly behave when you're looking at a milliliter, right? Like a thinker, a thimble of tissue. But when, you know, we want to sort of start integrating all of these different cell types, we're really limited by the raw material. And so, we've really been focusing the last three years on scaling up our raw material. Because the rates at which we can learn, we can print, we can divide and conquer all of these different questions. It's really fundamentally limited to our production of the cells. So, we are actually kind of putting our blinders on and running straight towards making 11 cell types all at heart scale. Not only will that allow us to start printing, you know, one big heart every two weeks is our goal, uh, for the purposes of practicing. But we can also divide all of those cell types to enable much higher throughput experimentation.

[00:16:26] There are so many variables that we need to control. What we're putting the cells in, how we mechanically train the cells, right? These heart cells need to eat and align strongly. How we electrically train them, right? What are they going to do when we add macrophages or immune cells into, uh, the tissue? How are we going to integrate the big vessels? How are they going to connect with the micro capillaries to make sure that every heart cell is within 20 microns of a microvessel? These are enormous challenges and having the variegate 11 different cell types that we know are important in the heart, having them at a good scale where we can conduct experiments that really depend upon a lot of cells.

[00:17:06] We're not able to do most of these experiments in a thin Petri dish, right? On 2D.

[00:17:10] Russ Altman: Right.

[00:17:10] Mark Skylar-Scott: Because their oxygen is not a problem. They're going to receive enough oxygen from above. We need to do this, you know, in fairly large tissues and with a lot of cells. And so, focusing on that scale up is just the rocket fuel for the rest of the project.

[00:17:24] Russ Altman: Yeah, it really makes sense. And I know that as a professor, it means that you don't have students who are waiting for these cells to do their experiments or who are competing with one another to get access to the cells. But if you have a big vat and if it's full, then, you know, a thousand flowers can bloom, and you can get the experiments done.

[00:17:40] Mark Skylar-Scott: A cornucopia of cells is the goal.

[00:17:43] Russ Altman: Yes, a cornucopia with a little squirting nozzle at the end of it.

[00:17:48] This is The Future of Everything with Russ Altman. More with Mark Skylar-Scott next.

[00:18:06] Welcome back to The Future of Everything. I'm Russ Altman and my guest today is Professor Mark Skylar-Scott from Stanford Bioengineering.

[00:18:13] In the last segment, Mark told us about this amazing capability to print 3D human cells to create things like the human heart. He outlined the 11 different cells that are needed and how we get them in the right place.

[00:18:26] In the next segment, he will tell us that vascularization, getting those blood vessels throughout the entire organ, is a huge challenge. Not to mention the ethics of doing this, and also, what's the timeline?

[00:18:40] So Mark, one of the things you said at the very end of the last segment was, every cell needs to be a certain distance from a blood vessel in order to get nutrients and oxygen. And so, there's this issue of how do you make sure that you get a totally functional vascularization of the tissue? That is to say, all of the blood vessels from the big ones down to the capillaries. Where are we with all that?

[00:19:02] Mark Skylar-Scott: Yeah, so this is a really crucial problem in tissue engineering and trying to manufacture human scale organs. And why? Because if we made a bucket load of cells, literally, like, you know, a quantity of cells and shoved them all in a bucket and had no plan to feed them with oxygen and nutrients, they would of course die, right? We have blood vessels throughout our body from the giant aorta right down to the tiniest capillary. And these supply the necessary oxygen and nutrients to every cell to keep them living. And if we don't have a plan in place to make sure that the cells we produce and compact together into the shape of a heart don't have it, a blood vessel network, ready in place, ready, connected to a pump, diffusing oxygen, sugars, nutrients to every, uh, cell in that tissue, it's going to die in, you know, a matter of hours.

[00:19:53] Russ Altman: Yeah, so this has to be there right away or very soon.

[00:19:56] Mark Skylar-Scott: It has to be there right away. Now, traditional tissue engineering, they take a sponge like scaffold and add seed, sprinkle cells onto that. And they're able to keep thin tissues living because there's Not enough thickness that to worry about oxygen diffusion. But when you want to manufacture a solid organ, these traditional approaches of tissue engineering really fall short in reproducing that 3D vascular network. And that is the key that 3D bioprinting is unlocking, our ability to create complex shapes from the cells the 11 different cell types I told you about. But also come into that tissue and right where the channels, the nutrient conduits will be for us to connect to a pump and keep those cells alive. Everything else falls apart.

[00:20:41] Russ Altman: Right.

[00:20:41] Mark Skylar-Scott: We have to deal with keeping those cells alive before we can think about anything beyond that. So, 3D printing can print the big vessels. But every single endothelial cell right down to the capillary, right? That's a blood vessel cells forming the tiniest capillaries. We aren't going to be able to print every single capillary network, there's far too many, far too dense in the heart. So, we will, and this gets back to what we just discussed earlier, we will rely upon some degree of self assembly, some degree of the cells knowing at the smaller scale how to connect those tiniest capillaries, relying on biological signals for angiogenesis, this process of tiny vessel creation. We will rely upon that, uh, to some extent. So, where the top-down 3D printed big vessels meet that Bottom-up self assembly, where biology rules at the sub-100-micron, sub 0.1 millimeter scale. That is a crucial problem that we are still working to try and solve.

[00:21:41] Russ Altman: So, is your sense that you're going to have the cells kind of burrow through the other cells to create the vessels? Or are you going to leave a hole in some way, like a little empty tube that they can then populate?

[00:21:53] Mark Skylar-Scott: We're trying both. I'm being very honest here. It's extremely difficult to get the capillaries to go through dense cardiac tissue. You'd think the cardiac tissue would say, hey, give me blood vessels, I need the oxygen.

[00:22:05] Russ Altman: Right, right. I like you, welcome.

[00:22:07] Mark Skylar-Scott: The reality is, for some reason, the endothelial cells, these blood vessel cells, kind of run away from the heart cells. They get pushed out and it's really annoying. It's very hard problem to solve. So, one strategy We're thinking about is creating the space for the cells to grow. And the other is working on the cell development to see are we missing something because we know this works in viva, we know this works in the body, but it does not work outside of the body. So, what are we missing? And that's sort of where our lab is putting a lot of efforts in.

[00:22:38] Russ Altman: So, it's all about vascularization and feeding those cells. Feed me, feed me.

[00:22:42] Mark Skylar-Scott: See more.

[00:22:43] Russ Altman: I want to switch tacks, uh, to, uh, the issue of ethics. Uh, this must raise ethical issues. You're taking human cells. Of course, you have nothing but honorable motives, but you could imagine other uses of this that might be less honorable. What is the status of the ethical discussion of printed organs? And, uh, what are the, I guess, what are the controversies, if any, in the field about the ethics of all this?

[00:23:09] Mark Skylar-Scott: So, we'll start at the stem cell, right? So, there's the embryonic stem cell, as you know, is a politically fraught entity. Uh, but we're fortunate that now that rather than relying upon fetal tissue, we're actually able to get the cells that we want from induced pluripotent stem cells. So, we can genetically engineer your own cell with your consent. Consent is extremely important with cell source, that the cells you're taking, uh, the patient knows exactly what you're going to do with it, how, what you'll use them for, making sure all those restrictions are documented and in place. But if you take a biopsy from a patient and turn it into their own induced pluripotent stem cell, they can form all the different tissue types that an embryonic stem cell can. And then I think this circumvents many of the ethical concerns that were present one or two decades ago in stem cell biology. The second concern is, I think, is access. This is not going to be cheap, right?

[00:24:04] Russ Altman: Right.

[00:24:04] Mark Skylar-Scott: It's lot of steps in making a heart and it's far more complex than making a small molecule and injecting that into a patient. Um, and because of the complexity, this, I don't think will be available broadly, even when technically feasible that it will be available broadly for a long time.

[00:24:22] Now that doesn't mean we shouldn't start putting the steps in place to make sure that what we are doing is as sustainable as possible and engineering here can play a big role. There's a big effort and we discussed it, we kind of touched upon it earlier with the lab grown meat industry.

[00:24:37] Russ Altman: Ya.

[00:24:37] Mark Skylar-Scott: There are a lot of people that are trying to make a lot of cells very affordably and very reproducibly. So, I think the economics is going to play in our favor over the next one or two decades to help with that. But it's definitely something we have to be mindful of as we develop something as complex of a printed organ.

[00:24:55] Russ Altman: I love your reference to the, um, to the meat, to the artificial or cultivated meat industry, because there are many examples in history of where some big commodity capability drives down prices. I'm thinking also about computer units, especially the GPUs that power AI now, they were created for games, uh, and now they're doing a lot more than just playing Nintendo.

[00:25:18] Um, and then the other thing I wanted to mention because you said about consent is it's very important because presumably you tell them, I'm going to take your skin cells, I'm going to make a heart. I promise not to also make brain tissue or other tissues that are not part of the plan. And I'm sure that your consents include language about the scope of use of these cells.

[00:25:39] Mark Skylar-Scott: That's right. And I would say we're fortunate in the heart space that we're not in as ethically fraught a space, perhaps as trying to engineer these cerebral organoids in a dish or trying to recreate blastoids, these blastocyst-like embryos, um, that are, um, uh, entities that are developing in a dish. So, we're not in that space. Uh, I think the heart is relatively more open waters from, uh, from an ethic standpoint.

[00:26:06] Russ Altman: Yes.

[00:26:07] Mark Skylar-Scott: And certainly, there is areas of research too. Its just people need to be careful with what, you know, what they're researching.

[00:26:12] Russ Altman: Great. So, in the final couple of minutes, I want to ask you about the timeline for all this. I'm sure there are people listening to us saying, I need that heart ASAP. Uh, other people might be young, and they may be many decades away from needing a new heart.

[00:26:25] What, can you give us a sense of what is the timeline that is a reasonable timeline for this kind of really quite amazing, uh, kind of unexpected in some way work?

[00:26:34] Mark Skylar-Scott: Yeah, everything we've described is still decades away, I would say. It's very blue-sky research. I'd say that's our role in academia is to think big and think broad and open, you know, open new avenues of investigation. So, this isn't something that's going to hit the clinic in the next one or two years for sure.

[00:26:51] But I think science can surprise us. I think we don't know what's going to be hard until we try it, and so, you know, there's certainly avenues where, you know, a decade plus is, this is feasible for first in human. You know, you have to remember that, uh, the need for an organ, the need for a heart is enormous. There are lots of patients that are not going to be eligible for a transplant, even though they need one, and so there's great grounds for compassionate use. So, risks can be taken if it's supported by good preclinical data. And so, our goal is to get that good preclinical data as soon as possible so that we can try and move this towards the clinic. But that is going to be a long process.

[00:27:33] Russ Altman: Um, that's fascinating. And I guess a corollary to that, obviously you're a leader in the field. Is the field gelling? Are we starting to see, I guess it's a funny question to ask, but are you happy with the number of competitors that you have? In the sense that this is creating a vibrant field where you're learning from each other, maybe competing a little bit? What is the state of the field?

[00:27:56] Mark Skylar-Scott: Yeah, I think in the bio fabrication field we're competitive collaborators.

[00:28:00] Russ Altman: Yes.

[00:28:00] Mark Skylar-Scott: I think we all understand the challenge is enormous to manufacture tissues, right? There's been a lot of promises made in tissue engineering, and I think it's worked out to be a lot harder than anyone expected 40 years ago.

[00:28:12] So there is a real cooperative spirit that we can all learn from each other. There's a lot of development. You know, there's every week there's new and exciting papers and methods and big moonshot attempts to make different tissues. Uh, so it is a very engaging field to be a part of.

[00:28:28] Thanks to Mark Skylar-Scott. That was The Future of Bioprinting.

[00:28:33] Thanks for tuning into this episode. With close to 250 episodes in our library, you have instant access to an extensive array of discussions on The Future of Everything. If you're enjoying the show and learning something useful, please consider giving us a five-star rating and a review to share your thoughts.

[00:28:50] You can connect with me on Twitter or X @RBAltman, and you can connect with Stanford Engineering @StanfordENG.