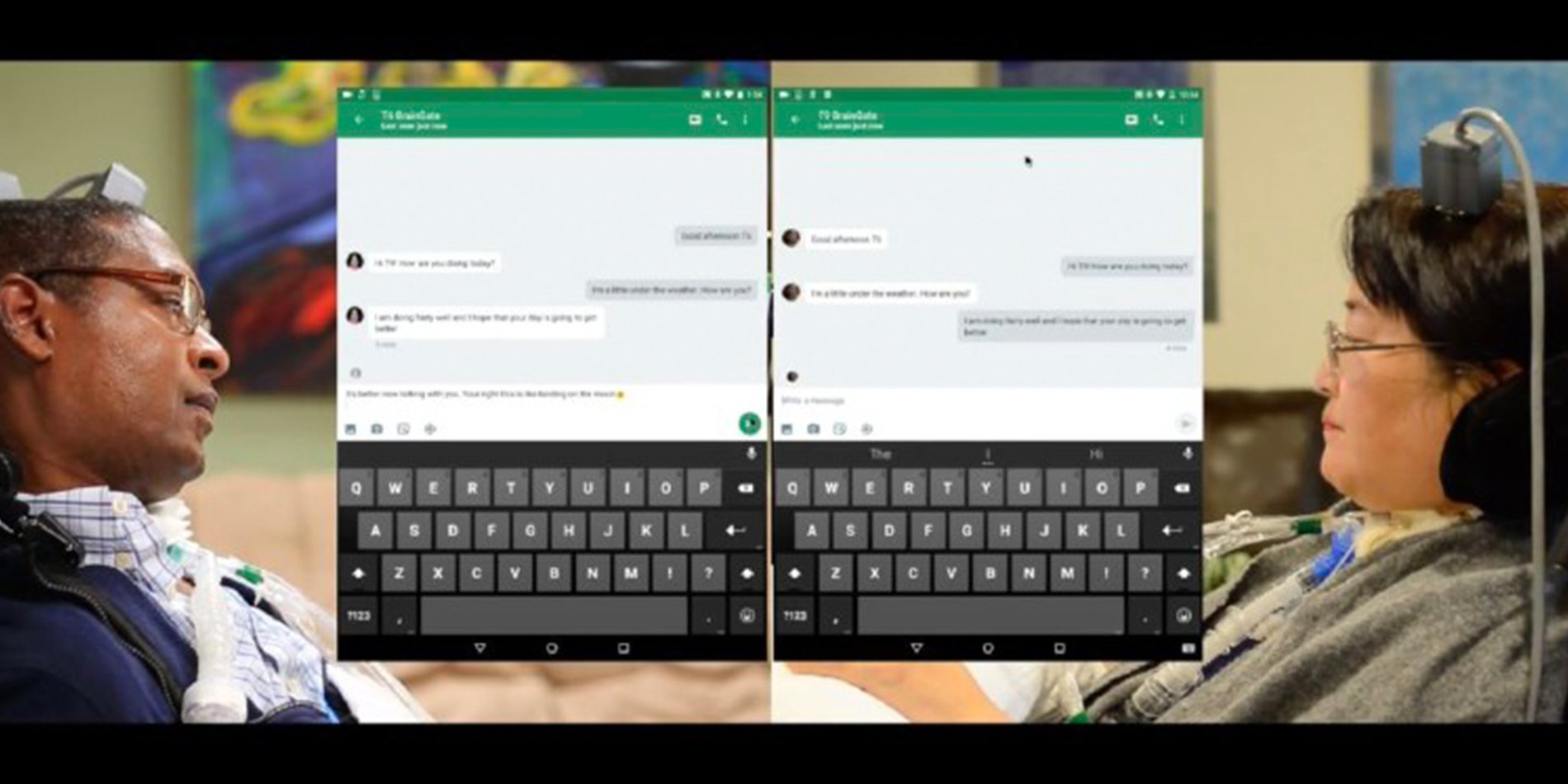

Patients with paralysis use brain signals to operate a tablet

New clinical trial results show that people with paralysis who have been equipped with a technologically advanced, baby-aspirin-sized brain implant can learn to directly operate an off-the-shelf computer tablet, just by thinking about making cursor movements and clicks on a wireless mouse paired to the device.

The implant-enabled trial participants were able to carry out real-world, real-time activities from web browsing or sending text messages and emails to shopping online, e-chatting, selecting videos and even playing music on a piano application.

In all cases, the tablet devices were entirely untweaked and had all pre-loaded accessibility software turned off.

The results are described in a paper in PLOS ONE co-authored by Stanford neurosurgeon Jaimie Henderson, MD; bioengineer Paul Nuyujukian, MD, PhD; electrical engineer Krishna Shenoy, PhD; and several collaborators at Stanford as well as at Brown University, Massachusetts General Hospital and Providence Veteran Affairs Medical Center, in an ongoing, interdisciplinary, multi-institutional consortium called BrainGate.

The trial involves three participants with severe weakness or total loss of movement in all four limbs, who have had small electrode arrays placed in their brains. The arrays pick up signals from the motor cortex, a region controlling muscle movements. These signals, which reflect intended movements, are then transmitted to a computer via a cable and translated into point-and-click commands guiding a cursor, allowing the participants to translate their intentions into on-screen actions.

Another paper published in early 2017 in eLife demonstrated that this assistive technology enabled these same three people to type just by thinking about it.

In the new trial, the participants learned to navigate through commonly used tablet programs, including email, chat, music-streaming and video-sharing apps. They messaged with family, friends, members of the research team and one another. They surfed the web, checked the news and weather and shopped online.

As skills increased, overt personalities blossomed. According to the PLOS ONE paper:

“[One participant] enjoyed messaging friends and family and watching videos... [A second] enjoyed using the musical keyboard. In fact, this was one of her earliest requests of the research team when she joined the study: to play music again. Providing her with a music keyboard interface on the tablet computer was as simple as installing an application from the Internet.

This participant, a musician, played a snippet of Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” on a digital piano interface.

A third participant said of his chat experiences, “[I] loved sending the message. Especially because I could interject some humor.””

Henderson, who performed two of the three implantation surgeries at Stanford Hospital, says. “It was wonderful to see the participants express themselves or just find a song they want to hear.”